Breakfast Blunder: How Popular Foods Can Lead to Inflammation and Health Risks

Breakfast foods such as croissants, cakes, pies and processed meats can contain refined carbohydrates and unhealthy fats that lead to inflammation. While these foods may be delicious, they can have…

Reducing Barriers: A Journey through Venture Capital, Electric Vehicles, and the Struggle for Progress

This week’s episode features a range of topics, including the challenges faced by venture capitalists in navigating red tape, the barriers to electric vehicle adoption, and political bias at National…

Generac Holdings’ Latest Breakdown: Failed Breakout or Late-Stage Base?

Generac Holdings (GNRC) experienced a breakout earlier, but has now fallen below the previous entry point of 133.15 from the cup with a handle formation. If a stock breaks and…

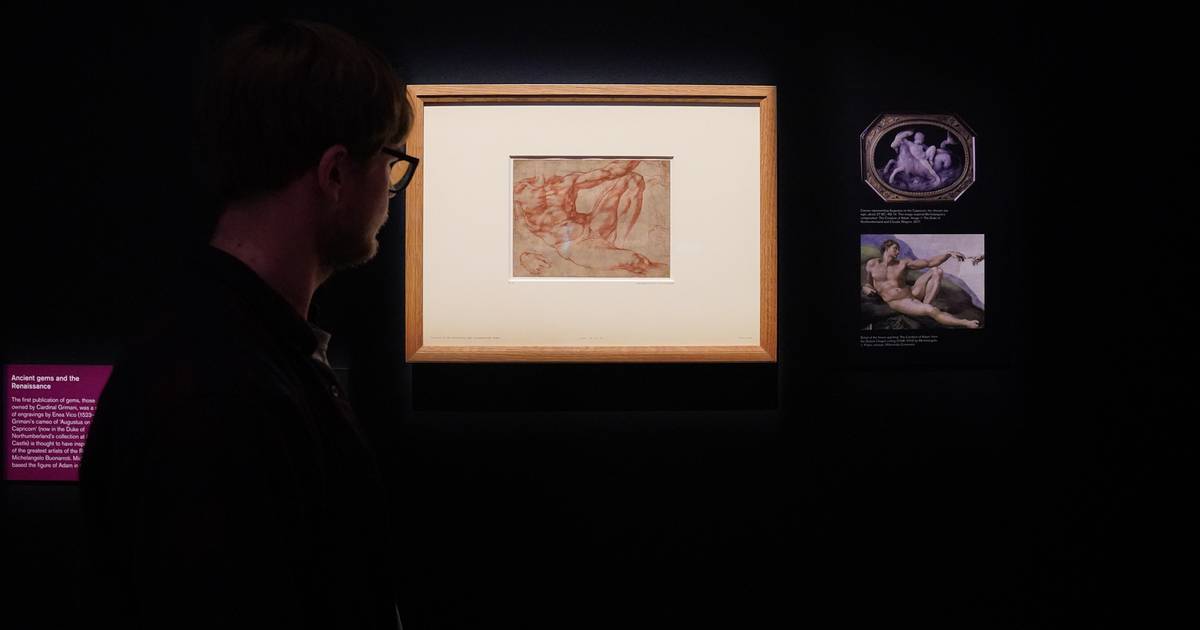

Michelangelo’s “Comparison” Drawing Sells for 33.6 Times Estimated Price at Christie’s Auction House”.

A small drawing on the back of a frame, accompanied by a letter from Michelangelo’s last direct descendant, was originally estimated to be worth between $6,000 and $8,000. However, New…

Revolutionizing Weather Forecasting: Nvidia’s Earth-2 Simulates the World for Accurate Predictions

In America, scientists have successfully created a “digital twin” of the Earth that can predict the weather more accurately than traditional services. This revolutionary platform, called Earth-2, was developed by…

Bronco Sport, Maverick Recall: Ford Issues Recall for Nearly 500,000 Vehicles Due to Battery Detection Problem

Ford has issued a recall for more than 456,000 Bronco Sport and Maverick vehicles due to a battery detection problem that could lead to a loss of drive power and…

Exploring the Red Planet: A Journalist’s Inside Look at Leading Mars Geology Team

As a journalist, I had the opportunity to lead the Geology team in our planned activities on Mars. Our schedule included a variety of targeted science at a distance, followed…

Vascular Expert Saves Mr. Minh’s Legs with “2 in 1” Intervention at Tam An General Hospital

Mr. Minh, a 75-year-old man, suffered from leg pain and difficulty walking due to blocked arteries in his lower limbs. The blockade posed a risk of severe anemia in both…

Critical Meeting Between US Secretary of State Blinken and Ukrainian Foreign Minister Kuleba to Discuss Urgent Need for Military Aid to Ukraine

On April 18, 2024, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba met to discuss the urgent need for military aid to Ukraine in the fight…

Revolutionizing Transportation: Jacksonville Takes the Lead in Autonomous Vehicles with FSC’s Driverless Shuttle

In recent years, autonomous vehicles have become increasingly popular and Jacksonville has taken the lead in this movement. Florida State College in the city has recently introduced a driverless vehicle…