Vinasun: Committed to Customer Service and Growth Despite Economic Challenges

Despite a significant drop in profits, Vinasun, a taxi company based in Vietnam, remains focused on improving customer service and attracting qualified employees. In the first quarter of this year,…

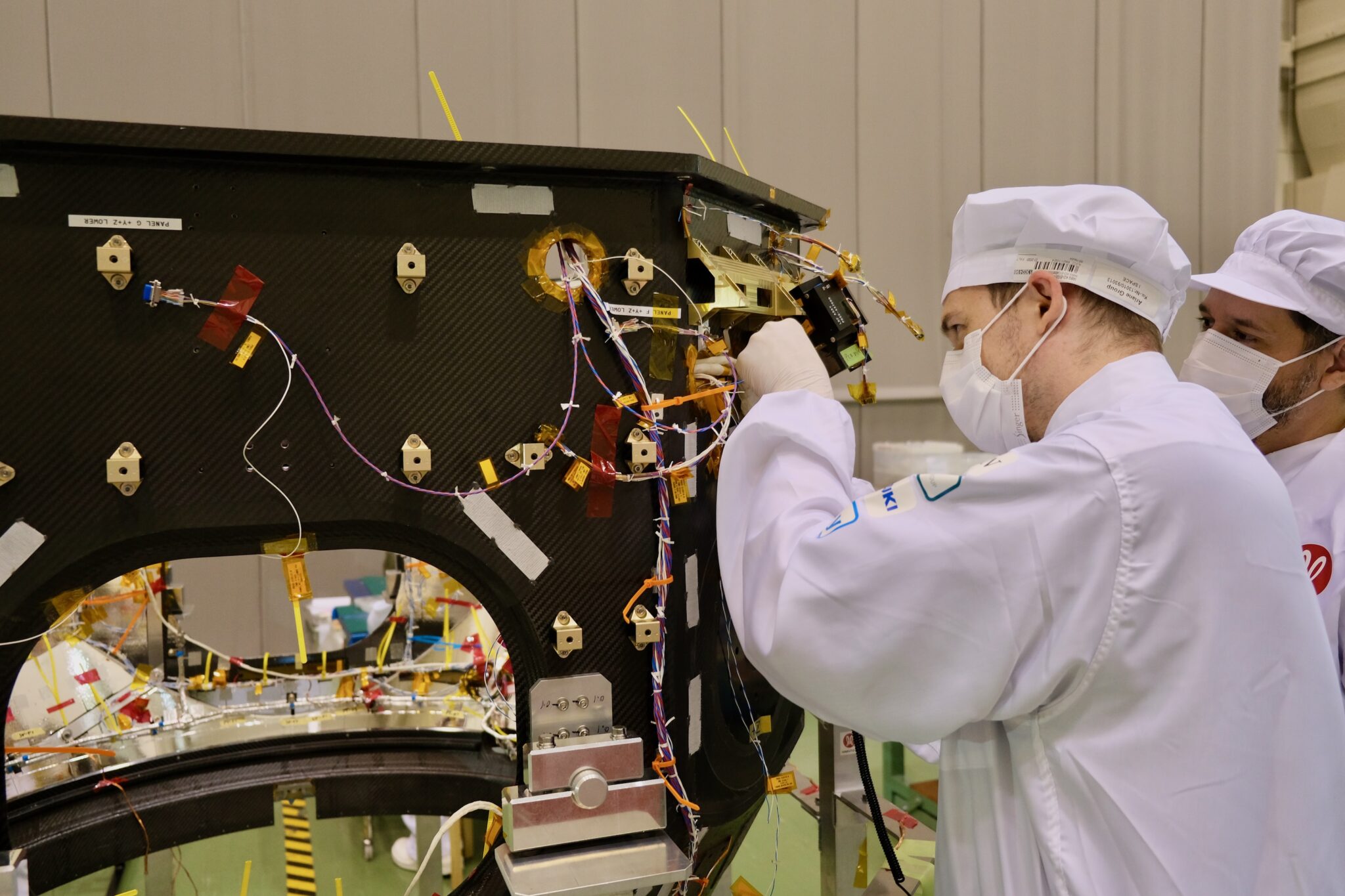

Japanese Space Agency Announces Plans for Satellite Communication System Around the Moon, Secures $45 Million Loan for Upcoming Lander Missions

At the Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium 2024, Japanese space agency officially announced its plans for a satellite communication system around the moon. This announcement was made just after the company…

Russian Strategists Allegedly Crafted AfD’s Political Positions, Report Claims

The SPIEGEL report claims that the AfD’s positions were formulated by strategists in Russia. According to the report, in September 2022, the head of the department was tasked with developing…

Fusion Technology awarded $159.8 million contract to improve FBI’s information services with Agile practices

Fusion Technology has been awarded a five-year, $159.8 million contract to assist the FBI’s Information Services Division in implementing Scaled Agile Framework practices and methodologies. This will help develop critical…

Brazilian soccer legend Marta announces retirement from international soccer: End of an era for women’s football

Brazilian soccer star Marta, who currently plays for Orlando Pride, has announced that she will retire from international soccer this year. At 38, Marta holds the record for Brazil’s all-time…

Hubble’s Gyroscope Glitch: One Solution, One Scope at a Time

In November, a specific gyroscope on the Hubble spacecraft caused it to enter safe mode due to erroneous readings. The team is currently working on a solution to resolve this…

Expanding to Two Locations: The MetroHealth System Men’s Health Fair is Back, Focused on Early Detection and Intervention through Free Screenings and Education

The MetroHealth System Men’s Health Fair will return this year, expanding to two locations on Saturday. The fair will offer a range of free health screenings, education, and career resources…

Rebuilding Together: Tkuma Directorate Announces $1.5 Billion for West Negev Settlements Reconstruction following Devastating Attacks

In response to the recent attacks on West Negev settlements, the Tkuma Directorate has announced a project to rebuild the affected communities. The ten hardest-hit settlements will receive NIS 1.5…

From Adversity to Triumph: A Virtual Panel Discussion on National Small Business Week and the Story of Selma’s Award-Winning Small Business Owner Jackie Smith

On Monday, April 29 at 3:00 PM CDT, U.S. Representative Terri Sewell of Alabama’s 7th District will host a virtual panel discussion to kick off National Small Business Week. The…

China Takes a Stand for Palestine: Supporting Unity Government with Hamas and Promoting Peace in the Region

The Chinese government has shown its support for the Palestinian Authority in its efforts to form a unity government with Hamas, despite years of conflict between the two groups. This…